Optimal Brain Quantizer - Pruning and Quantizing the Neural Nets

Neural Networks are computational models inspired by the human brain. They consist of layers of interconnected nodes (neurons) where each connection has a weight that adjusts as the model learns from data. But there is one problem with neural networks: they can be incredibly large and computationally expensive. These models can be very large in billion numbers of paramters, with many “details” (parameters) that help them make accurate predictions. However, when we want to run these models on devices with limited resources (like a smartphone), we need to make them smaller. This is where model compression techniques, like pruning and quantization, come into play. These techniques help reduce the size and complexity of neural networks, making them more efficient without significantly sacrificing performance.

One of the most advanced methods for model compression is the Optimal Brain Quantizer (OBQ), which is a framework designed to optimally reduce the precision of weights in a neural network through quantization. In this blog post, we’ll explore the concept of OBQ, starting from the basics and gradually moving towards the advanced mathematical principles that make it work.

What is Model Compression?

Before diving into OBQ, it’s important to understand what model compression is and why it’s necessary. In deep learning, a neural network consists of multiple layers of neurons, where each neuron is connected to many others through weights. These weights are typically represented by floating-point numbers, which offer high precision but require a lot of memory and processing power.

Model compression techniques aim to reduce the number of parameters (weights) in a neural network or the precision of these parameters. The two most common approaches are:

- Pruning: Removing some of the weights entirely by setting them to zero, which simplifies the network.

- Quantization: Reducing the precision of the weights, for example, by converting 32-bit floating-point numbers to 8-bit integers.

One of the challenges in model compression is performing these operations after the network has been trained, without retraining it. This is known as post-training compression. The goal is to take a fully trained model and compress it in a way that minimizes the loss in accuracy.

Overview : Optimal Brain Surgeon (OBS) Framework

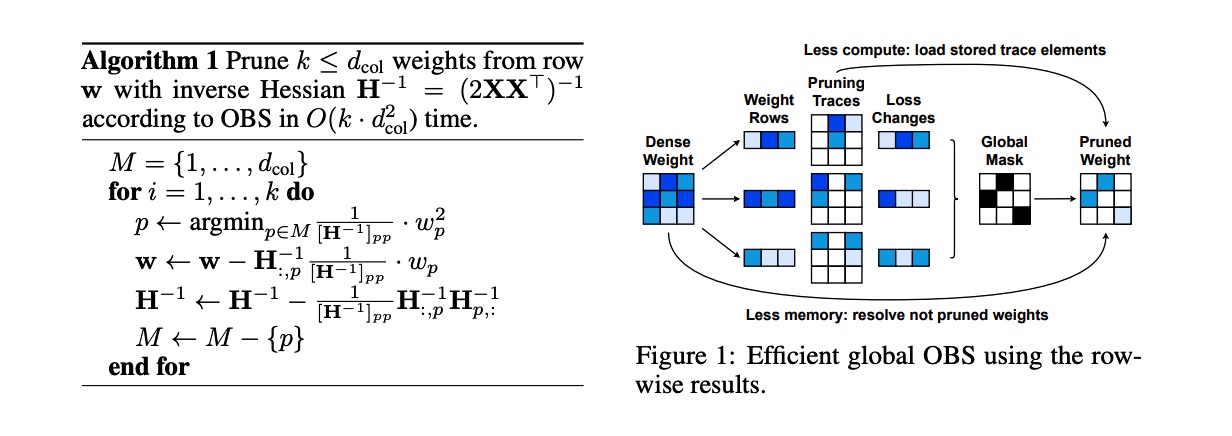

To understand OBQ, we first need to look at the Optimal Brain Surgeon (OBS) framework, which was originally developed for pruning neural networks. The OBS framework aims to identify and remove weights in the network that contribute the least to the overall performance. It does this by using second-order information, specifically the Hessian matrix, which provides insight into how the network’s loss function will change if certain weights are removed or altered.

The OBS framework operates under the following principles:

-

Loss Function: The loss function \(L(\mathbf{w})\) measures the difference between the predicted output of the neural network and the actual target values. It depends on the weights \(\mathbf{w}\) of the network.

-

Hessian Matrix: The Hessian matrix \(\mathbf{H}\) is a square matrix of second-order partial derivatives of the loss function with respect to the weights: \(\mathbf{H} = \frac{\partial^2 L(\mathbf{w})}{\partial \mathbf{w}^2}\) The Hessian provides information about the curvature of the loss function and helps identify which weights can be pruned with minimal impact on the loss.

-

Pruning Criterion: The OBS framework identifies the weight \(w_p\) to prune by minimizing the increase in loss: \(w_p = \arg\min_w \frac{w^2}{[\mathbf{H}^{-1}]_{pp}}\) Here, \(\mathbf[{H}^{-1}]_{pp}\) is the diagonal element of the inverse Hessian corresponding to weight \(w_p\).

-

Weight Update: Once a weight is pruned, the remaining weights are updated to compensate for its removal: \(\delta_p = -\frac{w_p}{[\mathbf{H}^{-1}]_{pp}} \cdot \mathbf{H}^{-1}_{:,p}\) where \(\mathbf{H}^{-1}_{:,p}\) is the \(p\) -th column of the inverse Hessian.

Diving deep into the OBS

Pruning a neural network is not as simple as chopping off random branches of a tree. Each weight in a neural network plays a role in shaping the model’s predictions. Remove the wrong one, and you could see a significant drop in accuracy. The key to effective pruning lies in identifying which weights are the least important and can be removed with minimal impact on the model’s performance.

This is where the Optimal Brain Surgeon (OBS) comes in. Unlike simpler pruning methods that might just look at the magnitude of weights, OBS uses a more sophisticated approach, leveraging the second-order information from the Hessian matrix of the loss function.

Mathematics behind the OBS

1. Loss Function and Taylor Expansion

Consider a neural network with weights \(W = [w_1, w_2, \ldots, w_n]\). The loss function \(\mathcal{L}(W)\) measures how well the network’s predictions match the target values.

At the heart of any neural network is the loss function, \(\mathcal{L}(W)\), which tells us how well the network’s predictions match the target values. The goal during training is to minimize this loss function by adjusting the weights \(W\).

To understand how pruning a weight affects the loss function, we can approximate the change in the loss using a second-order Taylor series expansion around the current weights \(W\):

\[\mathcal{L}(W + \delta W) \approx \mathcal{L}(W) + \nabla \mathcal{L}(W)^T \delta W + \frac{1}{2} \delta W^T H \delta W\]where:

- \(\nabla \mathcal{L}(W)\) is the gradient of the loss function with respect to the weights.

- \(H\) is the Hessian matrix, which contains the second-order partial derivatives of the loss function with respect to the weights.

- \(\delta W\) represents a small change in the weights.

2. Assumption of Small Gradient Term

At a local minimum (which is where the model typically resides after training), the gradient \(\nabla \mathcal{L}(W)\) is close to zero. Therefore, the term \(\nabla \mathcal{L}(W)^T \delta W\) is negligible and can be ignored. This simplifies our Taylor expansion to focus on the second-order term:

\[\Delta \mathcal{L} = \mathcal{L}(W + \delta W) - \mathcal{L}(W) \approx \frac{1}{2} \delta W^T H \delta W\]This equation tells us that the change in the loss function \(\Delta \mathcal{L}\) due to a small change in the weights \(\delta W\) is primarily governed by the Hessian matrix \(H\).

3. Change in Weights Due to Pruning

Suppose we want to prune (remove) a single weight \(w_p\) by setting it to zero. After pruning, the weight vector changes from \(W = [w_1, w_2, \ldots, w_n]\) to \(W_{\text{new}} = [w_1, \ldots, 0, \ldots, w_n]\). The change in the weights can be written as:

\[\delta W = W_{\text{new}} - W = [-w_p, \delta W_{-p}]\]where:

- \(\delta W_{-p}\) represents the change in the remaining weights after pruning \(w_p\).

4. Substituting the Change in Weights into the Loss Function

We substitute the expression for \(\delta W\) into the second-order approximation of the loss function:

\[\Delta \mathcal{L} \approx \frac{1}{2} \left([-w_p, \delta W_{-p}]\right)^T H \left([-w_p, \delta W_{-p}]\right)\]Expanding this, we get:

\[\Delta \mathcal{L} \approx \frac{1}{2} \left( w_p^2 H_{pp} + 2w_p H_{p, -p} \delta W_{-p} + \delta W_{-p}^T H_{-p, -p} \delta W_{-p} \right)\]Here:

- \(H_{pp}\) is the diagonal element of the Hessian matrix corresponding to \(w_p\).

- \(H_{p, -p}\) is the row vector in the Hessian that represents interactions between \(w_p\) and the other weights.

- \(H_{-p, -p}\) is the submatrix of the Hessian excluding the row and column corresponding to \(w_p\).

5. Neglecting Off-Diagonal Elements (Simplification)

In practice, the off-diagonal elements \(H_{p, -p}\) (which represent interactions between \(w_p\) and other weights) are often small and can be neglected, simplifying the equation to:

\[\Delta \mathcal{L} \approx \frac{1}{2} w_p^2 H_{pp}\]6. Using the Inverse Hessian for the Pruning Score

Instead of directly using \(H_{pp}\), which can be difficult to compute accurately, we use the diagonal element of the inverse Hessian matrix \([H^{-1}]_{pp}\). This gives a more stable and practical formula:

\[\Delta \mathcal{L} \approx \frac{1}{2} \frac{w_p^2}{[H^{-1}]_{pp}}\]The pruning score is defined as:

\[\text{Pruning Score} = \frac{w_p^2}{[H^{-1}]_{pp}}\]This score indicates how much the loss function will increase if weight \(w_p\) is pruned. The smaller the pruning score, the less the loss will increase, making \(w_p\) a good candidate for pruning.

7. Updating the Remaining Weights After Pruning

After pruning \(w_p\), the remaining weights \(W_{-p}\) need to be updated to minimize the impact on the loss function. The optimal update is:

\[\delta W_{-p} = - \frac{w_p}{[H^{-1}]_{pp}} H^{-1}_{:,p}\]This equation redistributes the effect of the pruned weight \(w_p\) across the remaining weights. The vector \(H^{-1}_{:,p}\) is the \(p\)-th column of the inverse Hessian, and the factor \(\frac{w_p}{[H^{-1}]_{pp}}\) scales this update.

Extending OBS to Quantization: The Optimal Brain Quantizer (OBQ)

While OBS is powerful for pruning, OBQ extends this idea to quantization—reducing the precision of weights rather than removing them entirely. The goal is to find which weights can be quantized with the least impact on the model’s performance.

1. Quantization Process

Suppose we have a weight \(w_p\) that we want to quantize. The quantization process can be represented as:

\[\hat{w}_p = \text{quant}(w_p)\]Where \(\hat{w}_p\) is the quantized value of \(w_p\). For example, if we are using an 8-bit quantization, \(\hat{w}_p\) will be an 8-bit approximation of \(w_p\).

2. Loss Function with Quantization

When we quantize \(w_p\) to \(\hat{w}_p\), the change in weights is \(\Delta W = (\hat{w}_p - w_p) e_p\). The change in loss due to this quantization is:

\[\Delta \mathcal{L} \approx \frac{1}{2} (\hat{w}_p - w_p)^2 \left[ H^{-1} \right]_{pp}\]This equation is analogous to the one used in OBS for pruning, where the goal is to minimize the loss increase by selecting weights for quantization in an optimal order.

3. Using the Inverse Hessian

Just as with OBS, instead of directly using the Hessian matrix, OBQ leverages the inverse Hessian matrix \([H^{-1}]_{pp}\) to quantify the impact of quantizing each weight. By minimizing the expression \(\frac{(\hat{w}_p - w_p)^2}{[H^{-1}]_{pp}}\), OBQ ensures that the most stable weights are quantized first.

4. Updating Weights After Quantization

After quantizing \(w_p\), the remaining weights need to be adjusted to compensate for the change. This adjustment is calculated using:

\[\Delta W_{\text{update}} = -\frac{(\hat{w}_p - w_p)}{\left[ H^{-1} \right]_{pp}} H^{-1}_{:,p}\]Where \(H^{-1}_{:,p}\) is the \(p\)-th column of the inverse Hessian matrix. This update ensures that the impact of quantizing \(w_p\) is distributed across the other weights, further minimizing the loss.

Example: Quantizing a Small Neural Network Layer

Let’s work through an example with specific numbers.

Consider a neural network layer with three weights \(w_1, w_2, w_3\). The loss function’s Hessian matrix (already calculated) is:

\[H = \begin{pmatrix} 2 & 0.5 & 0.5 \\ 0.5 & 1.5 & 0.25 \\ 0.5 & 0.25 & 1.0 \end{pmatrix}\]The inverse of this Hessian matrix is:

\[H^{-1} = \begin{pmatrix} 0.625 & -0.25 & -0.25 \\ -0.25 & 0.833 & -0.167 \\ -0.25 & -0.167 & 1.083 \end{pmatrix}\]The current weights are:

\[W = \begin{pmatrix} 1.0 \\ 0.5 \\ -0.5 \end{pmatrix}\]Quantizing \(w_1\)

Suppose we want to quantize \(w_1 = 1.0\) to \(\hat{w}_1 = 0.8\).

The change in \(w_1\) is \(\Delta w_1 = 0.8 - 1.0 = -0.2\).

The increase in loss due to this quantization is:

\[\Delta \mathcal{L} \approx \frac{1}{2} (-0.2)^2 \times 0.625 = 0.0125\]Next, we update the remaining weights to compensate for this quantization. The update for each weight is:

\[\Delta W_{\text{update}} = -\frac{-0.2}{0.625} \times H^{-1}_{:,1} = 0.32 \times \begin{pmatrix} 0.625 \\ -0.25 \\ -0.25 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 0.2 \\ -0.08 \\ -0.08 \end{pmatrix}\]So the new weights after quantizing \(w_1\) and updating the others are:

\[W_{\text{new}} = \begin{pmatrix} 0.8 \\ 0.42 \\ -0.58 \end{pmatrix}\]Iterating Over All Weights

OBQ would continue this process for \(w_2\) and \(w_3\), selecting the weight to quantize that minimizes the loss increase at each step, and updating the remaining weights accordingly.

Conclusion

The Optimal Brain Quantizer (OBQ) method provides a mathematically rigorous approach to quantizing neural network weights with minimal loss in accuracy. By carefully quantizing each weight and adjusting the remaining ones, OBQ minimizes the increase in error, allowing for effective model compression even in resource-constrained environments. This method is particularly powerful in post-training scenarios, where retraining the model is not an option, making it a practical tool for deploying complex models on devices with limited computational power.